Orthogonality

Orthogonality occurs when two things can vary independently, they are uncorrelated, or they are perpendicular.[[unclear]]

Contents |

Mathematics

In mathematics, two vectors are orthogonal if they are perpendicular, i.e., they form a right angle. The word comes from the Greek ὀρθός (orthos), meaning "straight", and γωνία (gonia), meaning "angle".

Definitions

- Two vectors,

and

and  , in an inner product space,

, in an inner product space,  , are orthogonal if their inner product

, are orthogonal if their inner product  is zero. This relationship is denoted

is zero. This relationship is denoted  .

. - Two vector subspaces,

and

and  , of an inner product space,

, of an inner product space,  , are called orthogonal subspaces if each vector in

, are called orthogonal subspaces if each vector in  is orthogonal to each vector in

is orthogonal to each vector in  . The largest subspace of

. The largest subspace of  that is orthogonal to a given subspace is its orthogonal complement.

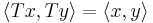

that is orthogonal to a given subspace is its orthogonal complement. - A linear transformation,

, is called an orthogonal linear transformation if it preserves the inner product, and thus the angle beween and the lengths of vectors. That is, for all pairs of vectors

, is called an orthogonal linear transformation if it preserves the inner product, and thus the angle beween and the lengths of vectors. That is, for all pairs of vectors  and

and  in the inner product space

in the inner product space  ,

,  .

. - A term rewriting system is said to be orthogonal if it is left-linear and is non-ambiguous. Orthogonal term rewriting systems are confluent.

- Curves or functions in the plane are orthogonal at an intersection if their tangent lines are perpendicular at that point.

A set of vectors is called pairwise orthogonal if each pairing of them is orthogonal; such a set is called an orthogonal set. Non-zero pairwise orthogonal vectors are always linearly independent.

In certain cases, the word normal is used to mean orthogonal, particularly in the geometric sense as in the normal to a surface. For example, the  -axis is normal to the curve

-axis is normal to the curve  at the origin. However, normal may also refer to the magnitude of a vector. In particular, a set is called orthonormal (orthogonal + normal) if it is an orthogonal set of unit vectors. As a result, use of the term normal to mean "orthogonal" is often avoided.

at the origin. However, normal may also refer to the magnitude of a vector. In particular, a set is called orthonormal (orthogonal + normal) if it is an orthogonal set of unit vectors. As a result, use of the term normal to mean "orthogonal" is often avoided.

Euclidean vector spaces

In 2- or higher-dimensional Euclidean space, two vectors are orthogonal if their dot product is zero, i.e. they make an angle of 90° or π/2 radians.[1] Hence orthogonality of vectors is an extension of the concept of perpendicular vectors into higher-dimensional spaces. In terms of Euclidean subspaces, the orthogonal complement of a line is the plane perpendicular to it, and vice versa. Note however that there is no correspondence with regards to perpendicular planes, because vectors in subspaces start from the origin.

In 4-dimensional Euclidean space, the orthogonal complement of a line is a hyperplane and vice versa, and that of a plane is a plane.

Orthogonal functions

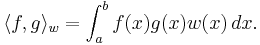

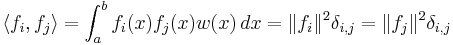

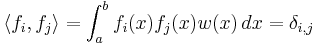

It is common to use the following inner product for two functions f and g:

Here we introduce a nonnegative weight function  in the definition of this inner product.

in the definition of this inner product.

We say that those functions are orthogonal if that inner product is zero:

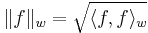

We write the norms with respect to this inner product and the weight function as

The members of a sequence { fi : i = 1, 2, 3, ... } are:

- orthogonal on the interval [a,b] if

- orthonormal on the interval [a,b] if

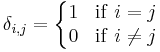

where

is the Kronecker delta. In other words, any two of them are orthogonal, and the norm of each is 1 in the case of the orthonormal sequence. See in particular orthogonal polynomials.

Examples

- The vectors (1, 3, 2), (3, −1, 0), (1/3, 1, −5/3) are orthogonal to each other, since (1)(3) + (3)(−1) + (2)(0) = 0, (3)(1/3) + (−1)(1) + (0)(−5/3) = 0, and (1)(1/3) + (3)(1) + (2)(−5/3) = 0.

- The vectors (1, 0, 1, 0, ...)T and (0, 1, 0, 1, ...)T are orthogonal to each other. The dot product of these vectors is 0. We can then make the generalization to consider the vectors in Z2n:

- for some positive integer a, and for 1 ≤ k ≤ a − 1, these vectors are orthogonal, for example (1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0)T, (0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1)T, (0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0)T are orthogonal.

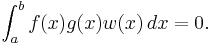

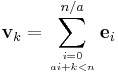

- Take two quadratic functions 2t + 3 and 5t2 + t − 17/9. These functions are orthogonal with respect to a unit weight function on the interval from −1 to 1. The product of these two functions is 10t3 + 17t2 − 7/9 t − 17/3, and now,

- The functions 1, sin(nx), cos(nx) : n = 1, 2, 3, ... are orthogonal with respect to Lebesgue measure on the interval from 0 to 2π. This fact is central to the theory of Fourier series.

Orthogonal polynomials

- Various eponymously named polynomial sequences are sequences of orthogonal polynomials. In particular:

- The Hermite polynomials are orthogonal with respect to the normal distribution with expected value 0.

- The Legendre polynomials are orthogonal with respect to the uniform distribution on the interval from −1 to 1.

- The Laguerre polynomials are orthogonal with respect to the exponential distribution. Somewhat more general Laguerre polynomial sequences are orthogonal with respect to gamma distributions.

- The Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind are orthogonal with respect to the measure

- The Chebyshev polynomials of the second kind are orthogonal with respect to the Wigner semicircle distribution.

Orthogonal states in quantum mechanics

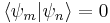

- In quantum mechanics, two eigenstates of a Hermitian operator,

and

and  , are orthogonal if they correspond to different eigenvalues. This means, in Dirac notation, that

, are orthogonal if they correspond to different eigenvalues. This means, in Dirac notation, that  unless

unless  and

and  correspond to the same eigenvalue. This follows from the fact that Schrödinger's equation is a Sturm–Liouville equation (in Schrödinger's formulation) or that observables are given by hermitian operators (in Heisenberg's formulation).

correspond to the same eigenvalue. This follows from the fact that Schrödinger's equation is a Sturm–Liouville equation (in Schrödinger's formulation) or that observables are given by hermitian operators (in Heisenberg's formulation).

Art and architecture

In art the perspective imagined lines pointing to the vanishing point are referred to as 'orthogonal lines'.

The term "orthogonal line" often has a quite different meaning in the literature of modern art criticism. Many works by painters such as Piet Mondrian and Burgoyne Diller are noted for their exclusive use of "orthogonal lines" — not, however, with reference to perspective, but rather referring to lines which are straight and exclusively horizontal or vertical, forming right angles where they intersect. For example, an essay at the website of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum states that "Mondrian ....dedicated his entire oeuvre to the investigation of the balance between orthogonal lines and primary colours." [1]

Computer science

Orthogonality is a system design property facilitating feasibility and compactness of complex designs. Orthogonality guarantees that modifying the technical effect produced by a component of a system neither creates nor propagates side effects to other components of the system. The emergent behavior of a system consisting of components should be controlled strictly by formal definitions of its logic and not by side effects resulting from poor integration, i.e. non-orthogonal design of modules and interfaces. Orthogonality reduces testing and development time because it is easier to verify designs that neither cause side effects nor depend on them.

For example, a car has orthogonal components and controls (e.g. accelerating the vehicle does not influence anything else but the components involved exclusively with the acceleration function). On the other hand, a non-orthogonal design might have its steering influence its braking (e.g. electronic stability control), or its speed tweak its suspension.[2] Consequently, this usage is seen to be derived from the use of orthogonal in mathematics: One may project a vector onto a subspace by projecting it onto each member of a set of basis vectors separately and adding the projections if and only if the basis vectors are mutually orthogonal.

An instruction set is said to be orthogonal if it lacks redundancy (i.e. there is only a single instruction that can be used to accomplish a given task)[3] and is designed such that instructions can use any register in any addressing mode. This terminology results from considering an instruction as a vector whose components are the instruction fields. One field identifies the registers to be operated upon, and another specifies the addressing mode. An orthogonal instruction set uniquely encodes all combinations of registers and addressing modes.

Communications

In communications, multiple-access schemes are orthogonal when an ideal receiver can completely reject arbitrarily strong unwanted signals using different basis functions than the desired signal. One such scheme is TDMA, where the orthogonal basis functions are non-overlapping rectangular pulses ("time slots").

Another scheme is orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM), which refers to the use, by a single transmitter, of a set of frequency multiplexed signals with the exact minimum frequency spacing needed to make them orthogonal so that they do not interfere with each other. Well known examples include (a, g, and n) versions of 802.11 Wi-Fi; WiMAX; ITU-T G.hn, DVB-T, the terrestrial digital TV broadcast system used in most of the world outside North America; and DMT, the standard form of ADSL.

In OFDM, the sub-carrier frequencies are chosen so that the sub-carriers are orthogonal to each other, meaning that cross-talk between the sub-channels is eliminated and inter-carrier guard bands are not required. This greatly simplifies the design of both the transmitter and the receiver; unlike conventional FDM, a separate filter for each sub-channel is not required.

Statistics, econometrics, and economics

When performing statistical analysis, independent variables that affect a particular dependent variable are said to be orthogonal if they are uncorrelated[4], since the covariance forms an inner product. In this case the same results are obtained for the effect of any of the independent variables upon the dependent variable, regardless of whether one models the variables' effects individually with simple regression or simultaneously with multiple regression. If correlation is present, the factors are not orthogonal and different results are obtained by the two methods. This usage arises from the fact that if centered (by subtracting the expected value (the mean)), uncorrelated variables are orthogonal in the geometric sense discussed above, both as observed data (i.e. vectors) and as random variables (i.e. density functions). One econometric formalism that is alternative to the maximum likelihood framework, the Generalized Method of Moments, relies on orthogonality conditions. In particular, the Ordinary Least Squares estimator may be easily derived from an orthogonality condition between predicted dependent variables and model residuals.

Taxonomy

In taxonomy, an orthogonal classification is one in which no item is a member of more than one group, that is, the classifications are mutually exclusive.

Combinatorics

In combinatorics, two n×n Latin squares are said to be orthogonal if their superimposition yields all possible n2 combinations of entries.[5]

Chemistry

In synthetic organic chemistry orthogonal protection is a strategy allowing the deprotection of functional groups independently of each other.

System Reliability

In the field of system reliability orthogonal redundancy is that form of redundancy where the form of backup device or method is completely different from the prone to error device or method. The failure mode of an orthogonally redundant backup device or method does not intersect with and is completely different from the failure mode of the device or method in need of redundancy to safeguard the total system against catastrophic failure.

Neuroscience

In neuroscience, a sensory map in the brain which has overlapping stimulus coding (e.g. location and quality) is called an orthogonal map.

See also

- Orthogonalization

- Orthogonal complement

- Orthonormality

- Pan-orthogonality occurs in coquaternions

- Orthonormal basis

- Orthogonal polynomials

- Orthogonal matrix

- Orthogonal group

- Surface normal

- Imaginary number

- Isogonal

- Isogonal trajectory

References

- ^ Trefethen, Lloyd N. & Bau, David (1997). Numerical linear algebra. SIAM. p. 13. ISBN 9780898713619. http://books.google.com/books?id=bj-Lu6zjWbEC&pg=PA13.

- ^ "Lincoln Mark VIII speed-sensitive suspension (MPEG video)". http://www.markviii.org/video/mark.mpg. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

- ^ Null, Linda & Lobur, Julia (2006). The essentials of computer organization and architecture (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 257. ISBN 9780763737696. http://books.google.com/books?id=QGPHAl9GE-IC&pg=PA257.

- ^ Probability, Random Variables and Stochastic Processes. McGraw-Hill. 2002. pp. 211. ISBN 0-07-366011-6.

- ^ Hedayat, A. et al (1999). Orthogonal arrays: theory and applications. Springer. p. 168. ISBN 9780387987668. http://books.google.com/books?id=HrUYlIbI2mEC&pg=PA168.

|

|||||

![\begin{align}

& {} \qquad \int_{-1}^1 \left(10t^3%2B17t^2-{7\over 9}t-{17\over 3}\right)\,dt \\[6pt]

& = \left[{5\over 2}t^4 %2B {17\over 3}t^3-{7\over 18}t^2-{17\over 3} t \right]_{-1}^1 \\[6pt]

& = \left({5\over 2}(1)^4%2B{17\over 3}(1)^3-{7\over 18}(1)^2-{17\over 3}(1)\right)-\left({5\over 2}(-1)^4%2B{17\over 3}(-1)^3-{7\over 18}(-1)^2-{17\over 3}(-1)\right) \\[6pt]

& = {19\over 9} - {19\over 9} = 0.

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/de26e139b955fa2cb5c953b32df52108.png)